MODERN MEAT

Modern Meat

Scroll

to read

Contents:

Introduction

Contents

Contributors

Development & Release

Prologue

Preface

Download for Free

Introduction

The 1st Textbook on Cultivated Meat

After designing the first course on cultivated meat at Stanford University in 2018, we began receiving messages from professors and students across the world about their interest in developing similar classes at their respective universities. As we began coordinating with interested institutions, a limitation for developing new courses on cultivated meat became clear - the lack of academic material on the subject.

By 2018, there had been dozens of research papers and even some books published on cultivated meat, but college curricula requires particular pedagogical rigor. A textbook was the type of resource that was needed to comprehensively cover cultivated meat; this would open new doors within academia for the subject matter. That’s what led us to begin the development of the first textbook on cultivated meat, Modern Meat.

Watch the original logo reveal here.

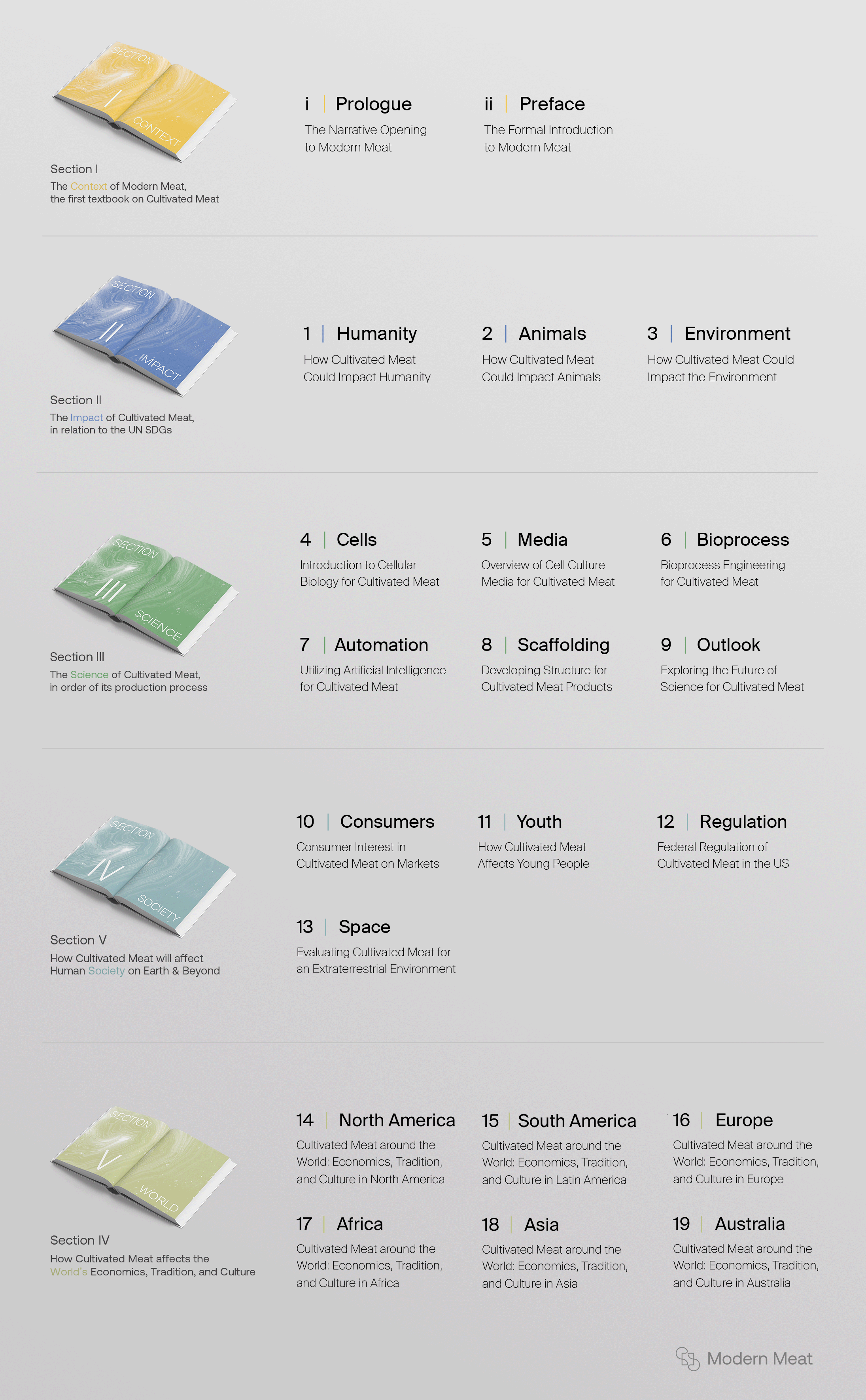

Contents

The Chapters of Modern Meat

This first edition of Modern Meat aims to pave the way for future courses on cultivated meat, serve as a guide to both newcomers & experts, and bolster cultivated meat’s growing academic sphere across the globe.

With such a wide audience, the textbook has to cover the full breadth of cultivated meat.

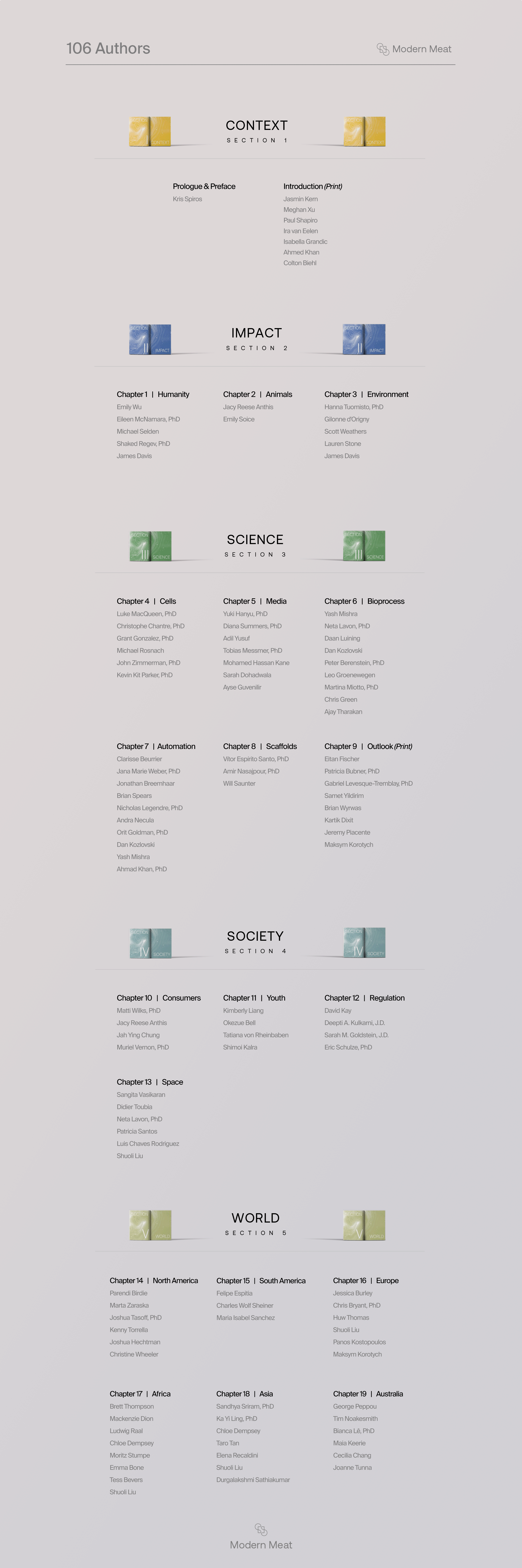

The Sections of Modern Meat, comprise 5 broad categories of cultivated meat: Context, Impact, Science, Society, and World.

The 19 chapters of Modern Meat, spread across these 5 sections, provide detailed entries on cultivated meat. They extensively tour a range of topics including the impact of cultivated meat on humans and animals, the bioprocess of cultivated meat production, how cultivated meat may become a food option in Space and on Mars, and how cultivated meat may impact the economy, culture, and tradition of Asia. This and much more can be found in the 19 chapters.

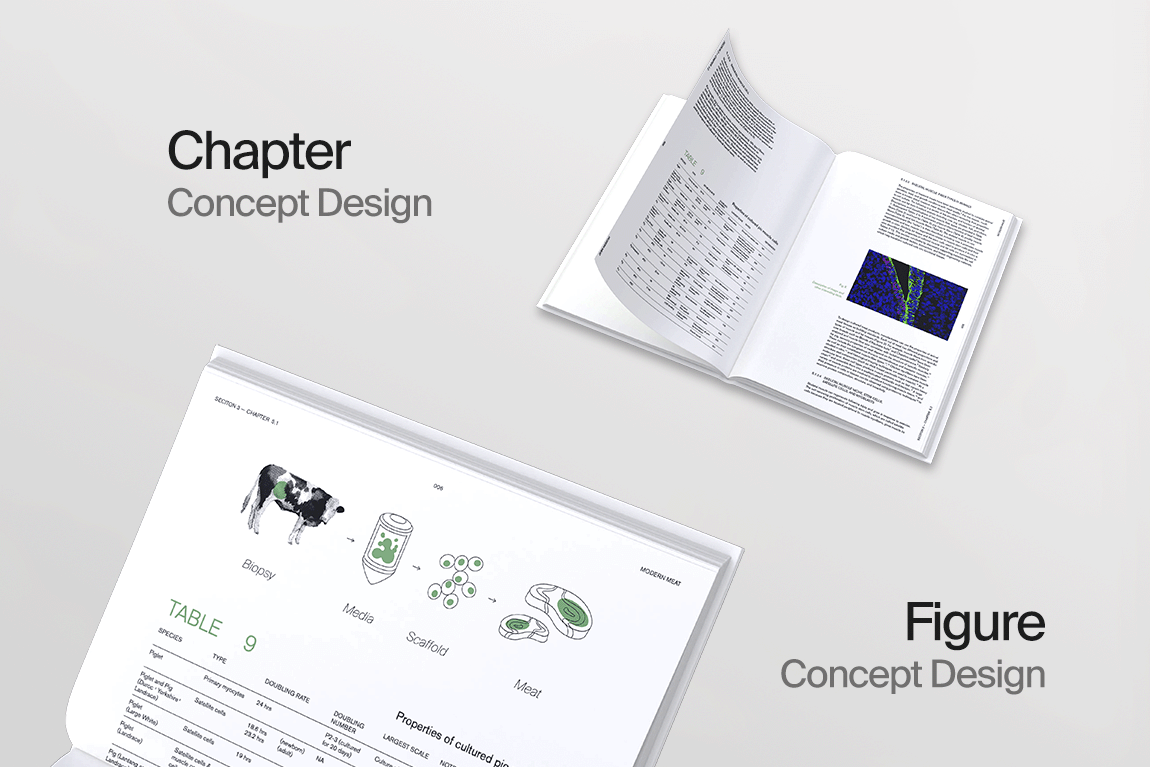

Each chapter also includes pedagogical elements to help navigate the nuance of cultivated meat in academic settings; this includes Outlines, Abstracts, Key Words, Fundamental Questions, Tables & Figures, and Further Reading.

**The Introduction & Outlook chapters can be found in the Print Version of Modern Meat

Modern Meat features the work of more than 100 authors, from academics to industry leaders, diverse and prominent voices from the cultivated meat community. Continue reading to learn about the many contributors to Modern Meat.

Contributors

100+ Authors Across Cultivated Meat

Modern Meat is presented on behalf of the leading cultivated meat companies from around the world, prominent nonprofit organizations, and the foremost academics across premiere institutions.

Opinions and beliefs presented on this website do not reflect the positions of these affiliates

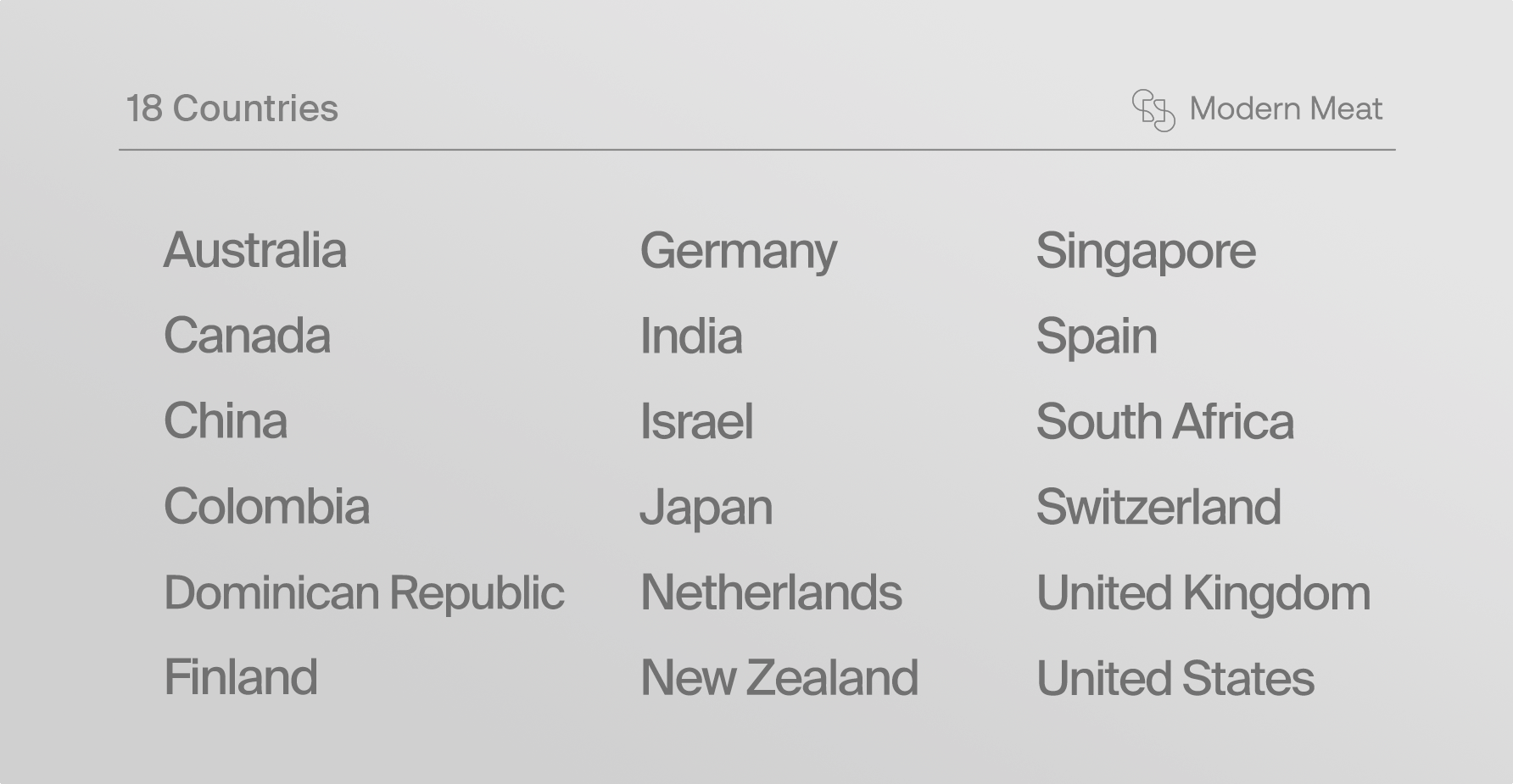

The authorship cast of Modern Meat spotlights a global authorship board with 18 countries represented.

The Members of the Editorial Board for Modern Meat are Kris Spiros, Sawyer Hall, Jane Darling, and Maya Benami, PhD.

Modern Meat required a global collaboration in cultivated meat at an unprecedented scale.

This project, half a decade in development, represents the largest collaboration in the history of cultivated meat. Contributors to Modern Meat include members of the MoMe Editorial Board, expert reviewers, and 100+ authors, all an extension of the world’s best expertise on cultivated meat, from the most influential companies, nonprofits, stakeholders, and academics.

Development & Release

5 years of Development & Future Print Edition

Modern Meat began with a vision for a global academic system that recognizes cultivated meat. As there are university departments and fields of discipline on animal agriculture, perhaps one day cultivated meat will have the same, and that begins with the concept’s first textbook.

Over the course of 5 years, we collaborated with the world’s top experts to create this first textbook on cultivated meat.

When the project began in 2018, we began by reaching out to our friends in the cultivated meat space, gauging who would be interested in helping pro bono to develop such a work. We graciously accepted the efforts of a few leaders, then a few dozen, and ultimately 100+.

It was important to incorporate a diversity of voices, but very critically, to enlist the support of the startups working on the cutting edge of cultivated meat. The industry was young; just a couple dozen startups existed in the world and collectively, they had raised just under $200M total. An insurgence of investor and public interest would takeoff shortly after, however.

This led to the beginning of a global industry that today includes more than 200 companies worldwide and over $2B of total investment.

This textbook represents a worldwide collaboration from the cultivated meat community, 5 years in the making. With the rapid change that occurred over 5 years, Modern Meat was constantly being updated by its many contributors.

But when Modern Meat’s development began, there were few notable examples of inspiration. Of course, there are countless textbooks that we could reference, but we quickly learned that finding the first textbooks on novel, world-changing subjects is rare. The closest, in relatively recent history, were the first textbooks on computer science and genetics.

But much of Modern Meat had to be conceived from the ground up. And great consideration was given to the audience and pedagogical approach.

Indeed, many contributors are passionate about cultivated meat one day becoming a successful product on the market, but this textbook did not serve as a conduit for such passion. Even though there can be a natural tendency to write as an advocate instead of an unbiased reporter of information, it was critical that Modern Meat spoke objectively about cultivated meat’s prospects. We hope that you find the text explores such nuance with honesty, and appropriately displays both positive and negative angles, culminating in a necessary neutral approach.

This was a critical, primary goal – create an objective piece of literature that covers cultivated meat, comprehensively, and does not serve as an outlet for advocates.

And when they aren’t writing, many authors of Modern Meat are building the industry of cultivated meat as founders, executives, and scientists. We sought their support to build Modern Meat because they are best suited to convey the concept they created.

While Modern Meat began as a book project to be published by a top global publisher, we decided after a few years to open-access publish the textbook. This felt in line with the From Fauna philosophy of creating free, widely accessible educational resources on cultivated meat. We are gracious for Oxford ORA’s system in helping us do that.

As we departed from a physical publisher, however, a gap emerged for a print-distributor for Modern Meat. We had already begun an extensive art direction period with our design partners at monopo, shown below; together we fully explored cover, section, chapter, and figure designs.

In 2023, 5 years since its inception in 2018, Modern Meat concluded its development with the release of the first digital edition. The project aims to open academia’s consideration for cultivated meat courses and other educational material all around the world.

Special thanks to Satish and Jay Karandikar, the creative team at monopo, and the countless others who have helped with this endeavor.

While the free, digital version of Modern Meat is published through Oxford ORA (link below), released as of March 9, 2023, we do plan to eventually produce a print-edition, featuring the aforementioned full-design treatment.

If you are a member of or have connections in the publishing industry, we would love to hear from you. Feel free to reach us at info@cellag.org.

The cultivated meat space is very fast-moving, and so, we always joked internally that the day Modern Meat was published, was the day it would be outdated. With that said, while the print-edition for this 1st version of Modern Meat is our initial focus, and the 2nd edition is not yet in development, we do plan for future editions of Modern Meat to be updated with information that is the state of the art for cultivated meat. We also think future LLMs might replace the necessity for future editions of the textbook.

Prologue

The Narrative Opening to Modern Meat

The following two sections represent the opening to Modern Meat, the Prologue & Preface. You can continue reading below, or view them by skipping to the full textbook, found at the link at the bottom of this webpage.

**The following years are approximated, fictional for literary purposes; while Modern Meat’s Prologue is based in real history, stories are not intended to relay the past with perfect accuracy

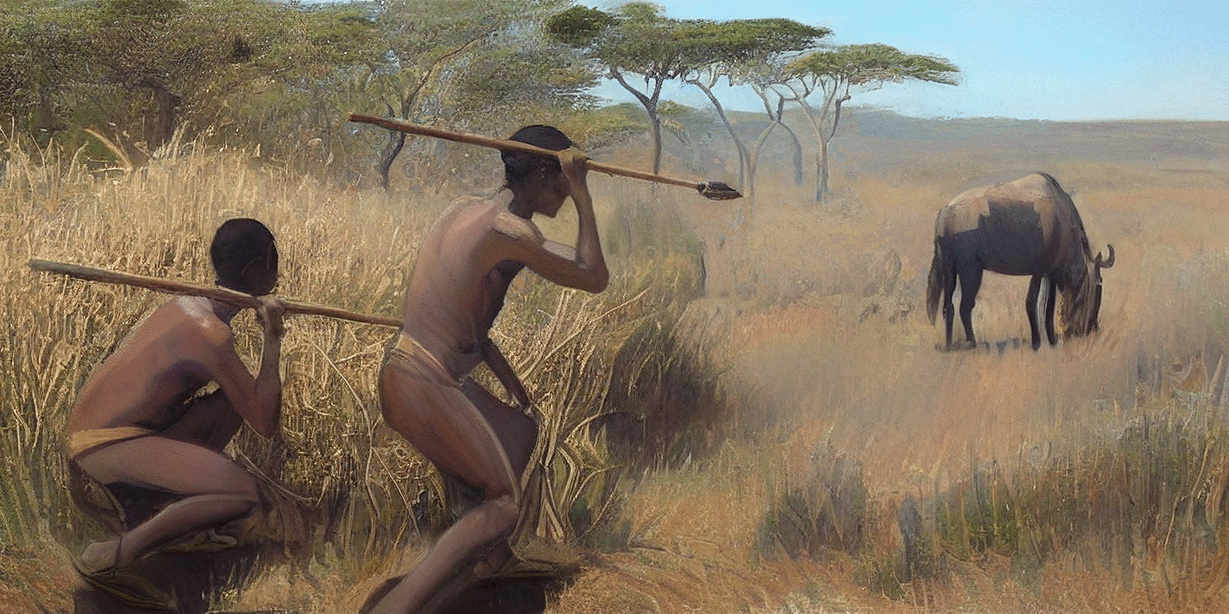

The year is 90,318 B.C.E.

A small group of hunters roam the plains of Africa. Having not eaten in days, they are as hungry as they are determined to track down a fitting prey. They carry spears and stones, crafted with precision for the task at hand. After a search, hours long, complete with life-dependent calculation, they scout a lone wildebeest. The animal is likely old or injured as it walks alone, far away from the pack, vulnerable. Tactically coordinated, the predators make their strike and kill the lone wildebeest.

This single animal and the meat that comes from it holds immeasurable value, but fundamentally, this successful hunt translates to survival for these early humans. They bring back the reward to their tribe, where this densely nutritious food is brought upon a fire, satiating ancestral appetites. That is, until they must go out to hunt again for their next meal.

This was meat. And the process of obtaining it. African hunters killing a wildebeest, representing the modern state of meat to pre-agricultural people.

This was modern meat 100,000 years ago.

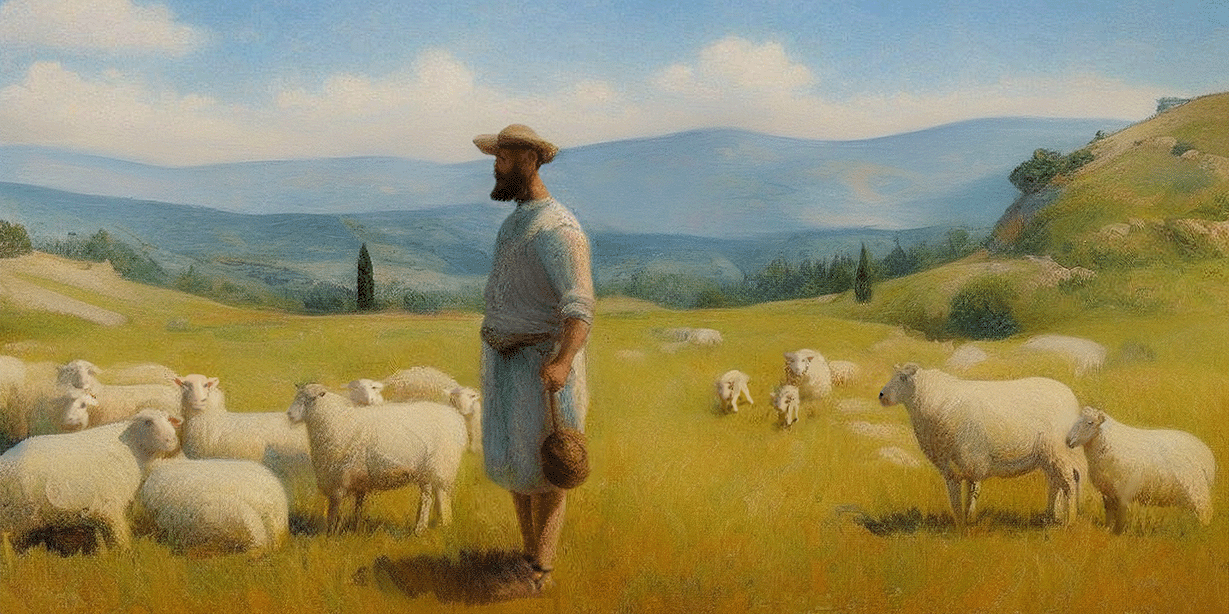

The year is 9,318 B.C.E.

An Asian farmer named Buwei herds his livestock along the Yangtze River. His village recently experienced a devastating wildfire, and in the process, much of his community’s agricultural supply has suffered. To accommodate and prevent a local famine, Buwei must select more animals than he planned for tomorrow’s slaughter.

Little does he know, Buwei is one of the first farmers on Earth – one of the first humans to practice the techniques of animal rearing that will fuel civilization for millennia to come. He’s also versatile with his agricultural skills, doubling as a cattle farmer and fisherman; he’s refined his fishing and herding techniques over decades, leading to pivotal moments like this where his community depends on him.

The next morning, Buwei sets out early, patiently fishing on the Yangtze till noon; in the afternoon, after taking stock of his herd, he inspects those best suited and slaughters 3 cattle, a third of all his animals.

Buwei does not work alone; almost everyone in his community plays a role in the meat preparation process. Buwei and his fellow ancient farmers approach this early form of meat production with a variety of skills – they collectively contribute to each part of the preparatory process, including handling, slaughtering, skinning, washing, and eventual cooking of the bovine meat.

At this time, it really does takes a village to raise animals for food.

This version of meat & animal husbandry notably contrasts that of the African hunters; there was great distance between the hunters’ homes and where they sought meat. But the advancements of agrarian society have brought animals into the villages themselves; this has meant closer quarters between the first animal farmers like Buwei and their livestock.

And this closer relationship with food comes as no surprise – the majority of humans on Earth, now totaling a population of almost 5 million, must take on agricultural-related work for collective survival.

Noteworthy too, farmers like Buwei are beginning to use tools such as ropes and fences to maintain his herd; indeed, the earliest roots of animal agriculture are sprouting.

This was meat. And the process of obtaining it. Buwei harvesting fish and slaughtering 3 cattle in his village in pre-historical China, representing the modern state of meat to early-agricultural people.

This was modern meat 10,000 years ago.

The year is 931 B.C.E.

It’s the early summer in Attica, Greece, and on a sunny morning, a shepherd named Ophelos rounds up his herd. Kronia, a summer festival, nears and he’s one of the main suppliers of lamb for the local market, the third-largest in Athens. He slaughters 18 sheep and prepares the meat with modern techniques he learned from his father.

After thousands of years, the domestication of animals has become commonplace; farming these sheep for meat is practiced generationally. Agricultural success comes easily to Ophelos and his fellow ancient Greek farmers, or at least as often as Demeter’s blessings are accounted for.

Meanwhile, the human population on Earth has increased in magnitude, now over 50 million. While animal farming techniques have increased in complexity, efficiency has meant fewer and fewer people are needed for labor, the diversity of civilization a result.

Nevertheless, all conquer their carnivorous palates through the work of farmers like Ophelos, regardless of their increasingly unique lives in the arts and government. The amplified capacity for trade and transport have also made it possible for not only Ophelos’ neighbors in his polis to be his customers, but also people in nearby regions, all get to experience his lamb.

This was meat. And the process of obtaining it. Ophelos slaughtering 18 sheep on his farm in Ancient Greece, representing the modern state of meat to ancient civilizations.

This was modern meat 1,000 years ago.

The year is 1923 C.E.

On a cold autumn morning in Los Andes, Chile, a farmer named Eduardo lets his pigs out of their stalls. With the help of his children, he then tends to his chickens. Eduardo’s father taught him a crafty way to keep the local foxes from getting to the hens; today he’s teaching his son and daughters. The expansiveness of his family farm allows Eduardo to manage a variety of livestock across his land. Even still, he holds less than a couple hundred animals total, not including the occasional fishing he enjoys in the Aconcagua River in his spare time.

Simply put, farming is Eduardo’s heritage; this Chilean family farm has been passed down from generation to generation. He learned everything he knows from his parents, and he teaches his children on a daily basis about how to operate the farm to take care of their future families. Eduardo’s farm provides meat not just to communities along the Aconcagua, but across the entirety of Chile. And while his method of pasture farming, animals grazing on the open Chilean plains, is representative of the norm for animal agriculture in 1922, meat demand is rising across South America.

Eduardo learns that some of his peers beginning to modify the organization of their farms into so-called feedlots and concentrated animal feeding operations. This effort is being led by once small family farms who have now merged into large, conglomerate meat companies. They offer help to small family farms like Eduardo’s, to evolve and use their new methods, methods that will allow his farm to breed and manage many more farm animals. With their proposed breeding techniques, as well as moving his animals from the outdoors to indoors, his farm could go from a couple of hundred animals to thousands. This translates to higher rates of meat production to feed an exponentially growing continent and world, but for him, it could mean feeding more people and making more money to take care of his family.

This proposition from the meat company comes at a cost though, and Eduardo is conflicted. There’s much tradition in his familiar operation of his farm. The practices

he’s followed his whole life, taught to him by his elders, are basically his pedigree. He’s accustomed to being outdoors with his animals, and moving everything into buildings feels unconventionally confining, both literally and figuratively. But the promise of feeding more hungry people, as well as the financial incentive of industrializing his farm is becoming more difficult to turn down.

Over the years, Eduardo sees the meat landscape becoming more competitive because many of his peers are taking on the new methods. They produce more and more meat while his production remains stagnant. The larger meat companies have helped install their methods across small family farms, adjacent to Eduardo’s. In exchange for farmers increasing their overall meat production using the innovative methods, the meat conglomerates have held true to their promises of increased distribution of the farmers’ meat products, as well as higher incomes for them and their families.

With these innovations in animal agriculture becoming more popular and meat’s demand continually rising, they begin to offer contracts to family farms, increasing competition. They promise good money if farms can match the capacity they’re looking for, really only possible with their proposed industrialized methods. How can Eduardo supply hundreds of pounds of pork per week when he still only has a few dozen pigs? How can he match the prices of his counterparts while he still pasture-raises his animals? He’s beginning to think he has no choice but to join the architecture of industrialized animal agriculture – for if he doesn’t, his farm will die and his family will suffer.

This situation is not unique to Eduardo in the 20th century. It’s becoming increasingly necessary to industrialize animal farming to maximize meat output; the global population is nearing 2 billion. And while traditions are being left to the wayside, a mass transition away from pastures indeed will help meet the rising demand for meat in Chile and beyond.

Nevertheless, for now, Eduardo must continue running his family farm the way he knows how. While the meat landscape is changing, they still have a lot of hungry customers, and a large order just came in for pork, chicken, and eggs. He’ll discuss the farm restructuring with his wife over the upcoming weekend, but for now customers await. With the help of his wife and children, they follow the same farming practices that past generations did to feed their community in Los Andes, and beyond.

This was meat. And the process of obtaining it. Eduardo processing meat from his farm animals; 3 cattle, 9 pigs, and 18 chickens harvested on his family farm in Los Andes, Chile. This represented the modern state of meat in early 20th century civilization.

This was modern meat 100 years ago.

The year is 2013

It’s a spring afternoon at the Smithfield Hog Processing Plant in North Carolina, United States. Indeed, the inklings of industrialization that Eduardo saw the beginnings of have become mainstream. Conventional animal agriculture has undergone massive shifts. Animal farming has transitioned from individuals and family operations to that of corporations and shareholders. What was once 99% of the global population working in agriculture, has become less than 1%. Yet, meat demand is at an all-time high, globally.

At this particular plant in North Carolina, Smithfield Foods processes 32,000 pigs in a single day. The millions of pounds of meat produced here daily would have amazed the previous generations, especially the African hunters. What would have taken them a lifetime of strategy, life-risking brutality, and effort has been boiled down to a single slaughterhouse’s hourly production capacity.

A global population of now over 7 billion and meat’s popularity continuing to rise, means the millions of pounds of meat produced at this plant barely supply a percentage of the total meat demand for the residents of North Carolina alone. Indeed, Smithfield’s distribution expands outside of North Carolina, and even the United States. This giant of the meat industry has customers spanning not just the North American continent, but the globe, exporting billions and billions of pounds of meat per year to consumers worldwide.

This was meat. And the process of obtaining it. Smithfield Foods processing 32,000 pigs in a single day in North Carolina, United States. This represented the modern state of meat to early 21st century civilization.

This was modern meat 10 years ago.

Meanwhile, a new concept for meat production is being imagined, one that involves harvesting meat from farm animals’ cells instead of farm animals themselves. The pioneers of this idea, academics and soon to be Founders from around the world, are beginning to consider its potential for feeding an exponentially-growing world population. And just as Eduardo was forced to consider a century ago, the global meat industry of the early 21st century must consider if this re-envisioned production process for meat could eventually outdate its status quo of industrialized animal agriculture. They begin to rethink the use of animals to produce meat.

The year is 2023

Well, what ten years can bring…the developments of the last decade may pose a greater shift to the production of meat than the last 100,000 altogether.

What was once science fiction is becoming reality, and making meat from mere cells is now forming into an entire industry. Not a single company just a decade ago and minimal financial support has evolved into a landscape of more than 200+ startups across the globe, with over $2B of investment.

And while industrialized animal agriculture still reigns supreme, the embers of this new concept grow stronger by the day.

This is modern meat today…

Preface

The Formal Introduction to Modern Meat

The only constant about modernity is that it always changes in its definition.

What has been considered “modern” for meat has evolved alongside civilization for millennia – from hunting, to farming, to factories, meat’s increasing demand has called for agricultural innovation across the board. And with such history behind us, we now stand on the edge of monumental prospect.

Meat may be on the precipice of its most revolutionary leap yet, removing the animal as the instrument of production. This is what we will explore in this textbook - what could be the next step in our relationship with meat…growing it from cells.

It’s within this new relationship, that the farm animal, having always been so intimately involved as the functional unit from which meat was harvested, may largely be decoupled from the process. Instead, the cells of farm animals would be used to produce meat through cultivated meat, the process of farming animal products from cells instead of animals. This meat, real meat produced from cells instead of animals, is called Cultivated Meat, and it will serve as the focus of this textbook. You may have heard of some other terms for this concept, including cultured meat, clean meat, lab-grown meat, or cell-based meat to name a few.

At a surface level, the prospects of cultivated meat may appear both malevolent and benevolent in nature. Humanity may never need to slaughter another animal for food, nor tax the environment in the process of doing so, but in turn, there exists real threats to job loss in the agricultural industry and potential negative impacts on traditions and culture for which livestock farming is still an integral component.

But for better or for worse, the magnitude of this moment remains the same – cultivated meat could usher in the most dramatic shift in agricultural history, and we may just be years away from its mainstream introduction.

In this textbook, we will hone in on where the young industry of cultivated meat stands today. We will undertake a deep dive into a variety of topics, detailing the Impact, Science, Economics, and Cultural ramifications that this new process of producing meat could bring unto the world.

As we peer into the potential horizon of cultivated meat, many critical questions remain in the outlook of meat’s future. This textbook was not developed to tell you what the future of meat will be, but simply what it could be. What will meat look like in 10 years from now or 100? Will people view animals, or perhaps cells, as the origin of meat?

But modernity knows no past or future. At present, cultivated meat resides in the hands of select people, from the scientists and business leaders of cultivated meat startups, to their funders on Wall Street and regulators in Washington. However, these groups tell but the opening to this story; it is the billions of consumers around the world who will determine the fate of modern meat this century.

Within this textbook, you will learn about the concept of cultivated meat from a range of perspectives, including the world’s top industry leaders and academics. The former, work on the cutting edge of cultivated meat daily, shortening the gap between rhetoric and reality, and the latter, have explored the intricacies of cultivated meat for decades, far before the world would know it. The authorship cast of this textbook consists of almost 100 members of the cultivated meat community, from 15+ countries. They gathered to contribute to this single text, mapping out the concept that unifies them all.

Deceptively so, it is this concept that embodies abundant diversity. Beyond its illusion as a seemingly simple food product, meat entangles itself in complex matters of the modern world. For discussions on the future of public health, animals, and the environment require its inclusion, and meat underwriting the entirety of the human story means it has profound roots in the full breadth of history’s cultures and economies. It is these roots that elevate its status above a mere menu item and ultimately bring us back to the timeliness and history of meat.

The stories of the African hunters, Buwei, Ophelos, Eduardo, and Smithfield Foods illustrate that meat has indeed stood the test of time. All generations have experienced its service, regardless of the ways the process has evolved to harvest it. While the product has remained the same, how meat was prepared and brought to a tribe or a polis or a country has undergone much change. And now, the young concept of cultivated meat may be next in line to change the world. It makes the seemingly impossible possible: eating meat, without eating animals; a practice that may soon become synonymous with the modernity of meat.

We’re pleased to share with you this outlook on what may become modern meat in the coming decades, and how meat made from cells could change the global landscape of agriculture forever.

We present to you the first edition of Modern Meat, the world’s first textbook on cultivated meat…

Download for Free

Courtesy of Oxford ORA

Please click here to read Modern Meat, made publicly available by Oxford University.

Related projects